How I do playtests

February 5, 2018

I play a lot of indie games, as well as a lot of itch.io stuff– smaller, shorter and simpler games. What I often notice, though, is that some of these games have really tiny but frustrating issues that could’ve been prevented, or moments where I just get stuck thinking the game glitched out.

One tool you could use to help to avoid these frustrating moments is playtesting, which will help you to spot the most obvious issues in your game that could prevent enjoyment. However, playtesting will face you with the ugly faces of your game– especially the first few tests, where you can see all of your game’s shortcomings. It can be depressing, and might make you reluctant to do tests at all. This post urges you to press on, because playtests introduce the element that completes your game: the players.

You will need to move the game out of the bubble it’s being developed in. When you give it to someone else, you will learn new things about your own game. These can be either good or bad, informative or not really helpful. You’ll need to learn to deal with that. Don’t make it the player’s fault (‘You’re playing it wrong!’), instead, look at where it is going wrong on the design level, as objectively as possible. It is human tendency to do this— I find watching playtests embarrassing, personally. It can be scary, but in the end, it’s for the good of the game.

In this post I explain which playtesting progress works for me. I playtest my games from time to time, so having a structure for organizing it is pretty helpful. It was designed to be efficient: get as much useful info from tests while organizing as few of them as possible. I’m intending this post for people who want to get started with playtesting, so if you already have a procedure that works for you, please stick to it!

Setting up the test

I attempt to begin testing as early in development as possible. The sooner you know the game is hot or not, the more informed you can make decisions on things like scope, risk areas, or perhaps even to deem the project a failure and cancel it. (Also known as “Fail faster.”)

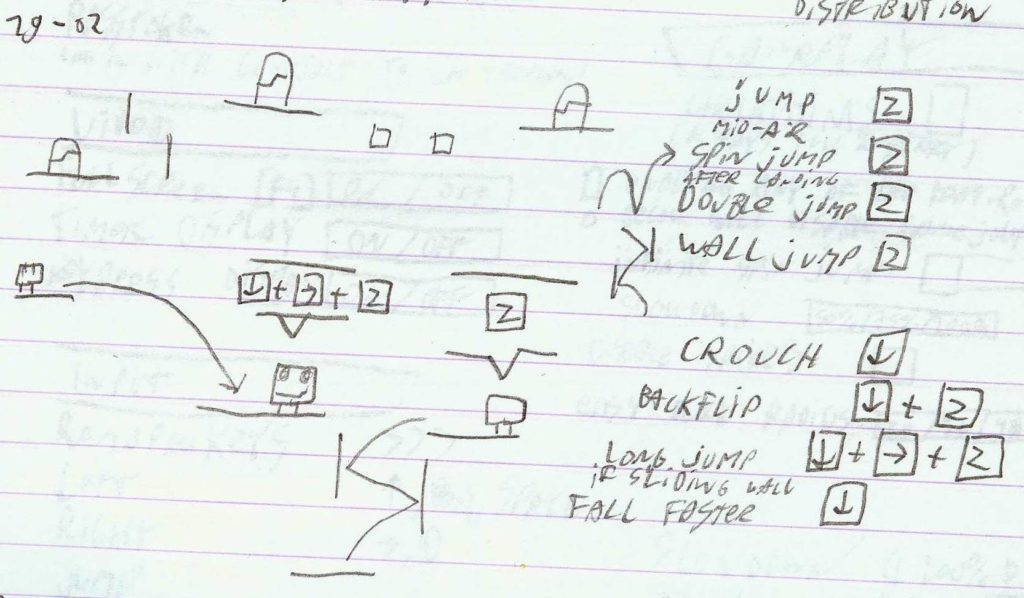

I have a notebook to make annotations while spectating the playtesters. With this you can quickly make notes, little drawings and diagrams. I would only use a keyboard if you’re an adept blind typer.

I also use notebooks for sketching ideas. Pro tip: date your entries to you can track your progress.

Make sure you have a stable build of your game to avoid a crash in the middle of the test. Note that a playtest and a bug test are two separate things– although you should note found bugs down to fix later. I do think you should compile/build your game beforehand, to make testing faster to set up. (You can still use the in-engine player as a Plan B.)

I record a video of the playtest to review it later if needed. You can either set up a camera to record the room and gameplay, or you can make your computer record its screen (see my tutorial for help with setting this up.)

During the test

Invite a friend, family member, or someone else you know (or a group if you have a multiplayer game), preferably people who haven’t played the game yet. (If you have trouble persuading someone to test, offering food could help.) If your game has a target audience defined, the perfect tester would be a part of that audience. I live in a small student house, so usually I sit in the living room to invite someone to test. Another thing I do is sending playtests per email, supplying browser-playable builds and requesting them to record footage. (I should note that friends and family are likely bad testers: they want to stay on your good side, so they won’t be honest if they think the game is bad. This is why I don’t just record literal feedback, but also pay attention to what they do and how they react to the game. More on this later.)

Generally, I try to avoid telling the testers anything in advance! No story, no controls, no rules, maybe a bit about the theme and genre to set the tone, or a logo or screenshot for email tests. So I interfere as little as possible (and preferably, not at all) during the test. (so-called ‘blind testing’.) I tell them the game isn’t done yet, so they can fill in the blanks I haven’t drawn in yet, and look past the more obvious shortcomings.

Then, I start the game, sit down, watch silently, and take a ton of notes. Distinguish your observations (things of interest you see happening) from the feedback you get (comments and suggestions given by testers). After testing, I ask them some questions. I rarely prepare those up front, but sometimes I’m testing specific new changes that require me to poke the tester a little to measure its effectiveness. Avoid closed questions (those answered with yes or no) for better feedback, and ask follow up questions if necessary. Always thank the tester, even if the feedback was negative, and I tell what I plan to do with the results to improve the game.

The more testers you can get, the better, though you should stop when tests give you less new information. I usually make one really polished build of the game and make sure two or three people play that, but more would be even better if you have the time.

Footage from a playtester who actively avoided checkpoints because of their similarity to the saws, making the game a lot harder than it needed to be.

Compiling feedback afterwards

Now I turn bits of info I obtained from the playtest into something useful that I can improve my game with!

First off, suggestions. People giving suggestions don’t consciously realize what the underlying problem is, so literally implementing their suggestion might cause new problems on top of existing ones. Sounds harsh, but I find this to be true. For example, if a player complains an enemy is too powerful, the obvious suggestion would be to lower its attack power. Upon further testing, you could discover that the problem lies elsewhere entirely– like a well-hidden bug that causes incorrect hitboxes, or enemies behaving unpredictably. Look beyond the surface level of these suggestions.

Then, the remaining feedback. The same goes as for suggestions: they know what emotions they have (which results in their feedback), but miss the exact cause(s) that triggered them. Again, it is up to designer to uncover this. For example, in Fortnite from Epic Games, designers stumbled upon an issue where players had difficulty aiming. If you’d take that at face value, you’d make the hitboxes bigger, right? After some more digging, it appeared that enemies took too sharp turns around obstacles, making it harder to predict where to shoot. Every problem might be deeper than how it seems initially, and it’s up to you to dig to the core of the issue.

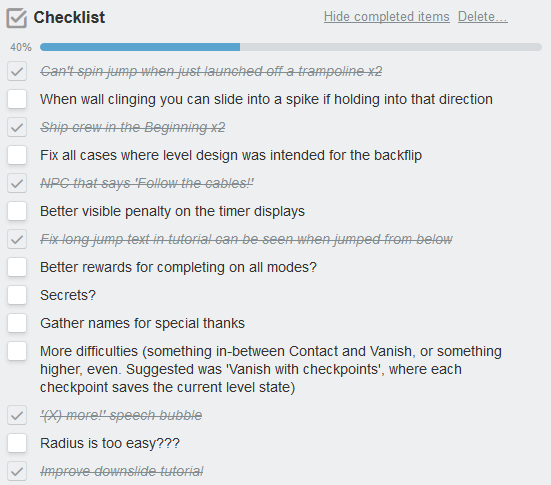

Finally, my observations. These might be small things I noticed (players bump their heads into one particular block) that know can fix easily, or bigger issues throughout the entire test (players keep bumping their head constantly) that you don’t really know the solution to yet. Put both on a task list to fix later.

Now I have an extensive list of tasks to fix! For me with two/three testers, these often range between the 30–40 items, varying in severity. Normally, I start a new test once all issues from the previous test have been fixed, to see if the issues actually disappeared, but you can do one anytime.

Alternative approaches

- Tell people the game is done, and that the version they’re testing is the version that will launch soon to get more honest feedback, even if it’s actually not even close to done. It worked, as example, for Slime Rancher.

- It might be interesting to make two players play a single player game together. They’ll constantly be in dialogue with each other, on which you can eavesdrop and gather interesting bits on how both players interact with the game.

- If you are not sure whether option A or option B is the best for your game, you can implement both and let one group play version A and another version B, then compare them to see which one is more fitting for your game. (This is called an AB test.)

- Analytics could work, but I only recommend this if you have too many players to analyze all tests separately. Note that stats rarely tell the stories behind them, causing you to miss potential issues, but there are interesting tools like heat maps that help sketching out the underlying problems.

- Asking random people to test your game is the best way to get honest feedback, but it’s rare to find willing strangers. There are really creative solutions for this problem, though– for example, here’s a story about playtesting at the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Further reading

Celia Hodent (Mostly user experience related, but has some good info on how players think about games and some snippets about playtesting. Especially the Gamer’s Brain series of talks is very good and a nice entry point into user experience, which is closely related to playtesting.)

Avoiding Evil Data (The designer of Hidden Folks has a more rigorous playtesting discipline, where playtests are held at high frequency. Very interesting GDC talk.)

Ideal amount of testers (This article argues that, if you test with five users, you’ll find 85% of all possible issues, which I think is a pretty good percentage. Debatable, but you could start off with this amount of testers.)

Tom Hermans

Tom Hermans